Fighting to Coach

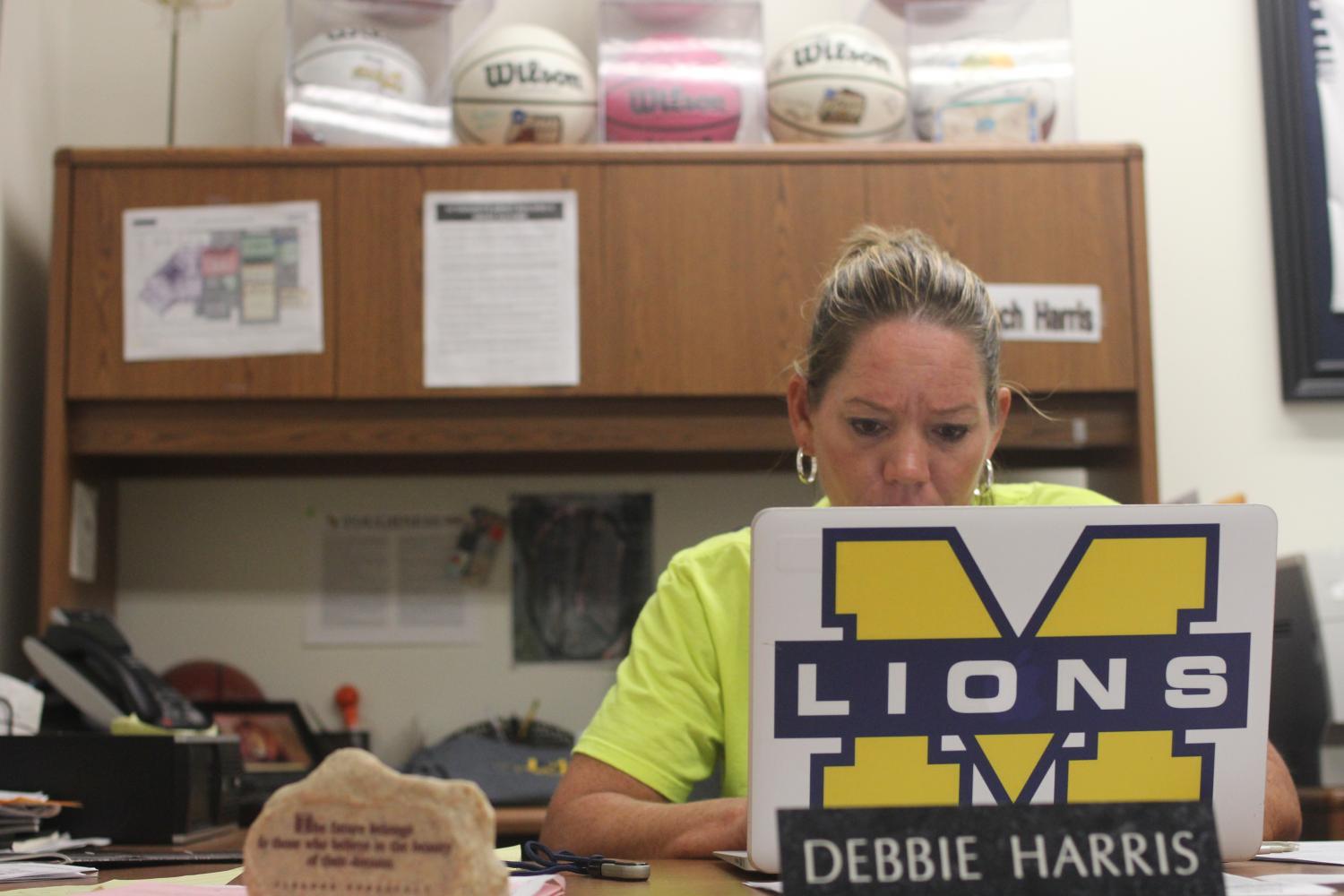

Deborah Harris worked hard to overcome adverse childhood, help kids

September 14, 2017

Breath reeking, voice hoarse, her father’s drunken rage felt never-ending. She watched her brothers take blow after blow, his yells drowning out all other sound, and decided she could not stay there any longer. Picking up the phone, she called her eighth grade basketball coach. And she spent the rest of that night playing Pac-Man in a pizza parlor with her coach, far from the home she never wanted to see again.

Girls varsity basketball coach and co-athletic coordinator Deborah Harris moved to Sonora, Texas at age five after her mother died from alcohol abuse. Her father, although working for the sheriff’s office, also struggled with alcohol and didn’t treat her or her two older brothers with any affection.

“He was very frustrated that he had three kids that he did not know anything about, or want anything to do with,” Coach Harris said. “So, there were some struggles at home, some physical challenges, and I kind of bounced around from place to place. Sometimes I’d stay in the park, wherever I could find a place, because it was easier than going home and being the target of something.”

She struggled through her childhood, and didn’t receive adult support until she reached middle school, when her best friend forced her to join the basketball team.

“My best friend, Danielle, was so excited about basketball,” Coach Harris said. “Me—I hated school, I hated people, and Danielle was the only person I talked to. I had no intentions of playing basketball. But, when the PE teachers asked us who would play basketball next year, Danielle was so excited with her hand up, saying ‘Raise your hand, raise your hand!’ and I said, ‘I’m not playing,’ so she lowered her hand. Then, I said, ‘You have to play basketball. You love this.’ And she said, ‘I’m not playing if you’re not playing.’ So I decided, crap, whatever, I’ll play.”

Coach Harris thought the coaches would eventually kick her out of athletics, knowing how they wouldn’t want to deal with her situation.

“I was way too proud to quit, and I ran, and I ran, and I was always in trouble, but they were not going to let me out,” she said. “They didn’t coddle me, or feel sorry, or make excuses, and I think they were harder on me than they were anybody else. But, I had that pride that I was not going to quit, that they were not going to break me. I was going to break them. And by the grace of God, that is why I am where I am today, because they had the foresight to understand that I was a child that needed some help.”

One specific coach, Terie Campbell, cared for her both on and off the court.

“I was in and out with my dad when I was in middle school, and she really got me out of some very bad situations,” Coach Harris said. “She wanted to do what was right for me. So she had no problems if I called her and there were things going on at the house. She’d just walk right through the door and get me, and take me out. When your dad’s a police officer, that’s a risk. But she didn’t care. She was going to do right by me. She has been a huge mentor in my life.”

Terie Campbell, now the golf coach at Hebron High School, recalls Coach Harris’s struggles.

“I didn’t ask any questions, or call her dad,” Coach Campbell said. “For her to trust me enough to come get her—for us to just chill—it meant a lot to me. I just wanted her to be a kid. She was missing out on just being a kid. And that’s not right. I had the perfect parents, and the perfect childhood, and her situation made my heart break. I wanted to do whatever I could to help.”

Coach Harris wanted to help kids just as Coach Campbell had helped her.

“That’s when I knew my mission in life was to be a coach and a teacher,” she said. “I still didn’t like school, but once I started basketball, I passed my classes so that I could participate. And when I found out that I had to go to college, obviously the financial issue was a struggle, so I was like, I hate school, number one, I don’t want to go to college, number two, and I don’t have any money, so I knew that athletics was my ticket to college.”

“That’s when I knew my mission in life was to be a coach and a teacher,” she said. “I still didn’t like school, but once I started basketball, I passed my classes so that I could participate. And when I found out that I had to go to college, obviously the financial issue was a struggle, so I was like, I hate school, number one, I don’t want to go to college, number two, and I don’t have any money, so I knew that athletics was my ticket to college.”

At first, she wanted to attend college as far away from Sonora as possible. Then, she found a reason to stay as close as she could.

“When I was a kid, I would watch moms, because I’d play a game in my head: if I had a mom, who would I want her to be like? Because I have very few memories of my mother, and none of them are good. So, this one lady had three boys, and she’d take them to church every Sunday, and I would go to church—I was ridiculed a lot by my brothers and my dad, but I knew that I needed to be a part of something. So, I’d sit in the back of the church, and I’d watch her. And just the compassion that she showed for her boys, I watched it for years.”

Her senior year of high school, she decided to tell this lady how much she had affected her life.

“I told her that exact story, how I would watch people, and it was an immediate—just, I can’t even put words to it—it was like God created that relationship,” she said. “She had always wanted a daughter, and she had three boys, and she had a similar story. She introduced me to her husband, and the boys, and it was like an instant. There was never any, ‘there’s a stranger in my house.’ It was, ‘Oh my gosh, I got a sister.’ It wasn’t until 18 when I found that, but it’s been the biggest blessing in my life.”

Billie Renfro, the lady who has been her mother ever since, feels a connection with Coach Harris that she felt with her own mother.

“She had a rough childhood, but I believe, even though Deborah and I don’t live in the same town or talk every day, we have the same mother-daughter bonding,” Billie said. “I feel like I got that chance, to have that daughter, even though she came later, I got that chance to have a daughter. And I feel the connection I had with my mother with Deborah. I feel that closeness to her.”

Having a family made her journey to college a little easier, but it still posed a problem financially. She applied for a Pell Grant, but her legal father had kept her on his income tax forms, so she had to provide evidence of her situation to qualify. Not to mention, he discouraged her from even trying.

“I didn’t know how to apply for college,” she said. “I didn’t know anything. It was a lot of self-direction, and I just kind of figured it out.”

She started out attending Hardin Simmons, then transferred to Angelo State University so she’d be closer to her new family.

“When I called my dad and asked him about taking me out of his taxes, he told me I would never make it in college,” Coach Harris said. “So, when it came time to graduate, I sent him an invitation on purpose to let him know that I did graduate. I graduated in four years. And I immediately got a job coaching after that.”

Since then, she’s coached at Midland, Irving, Southlake, Keller, and Fossil Ridge. She’s been at McKinney High for the past 12 years.

“I’ve found that we’ve had more and more kids with struggles,” she said, “and they need to look at a teacher, and say ‘Hey, you’re not this person that fits in this bubble. You’ve actually dealt with some of the things I’ve dealt with.’ And that connection is valuable.”

Being a coach has meant the world to her, since her own coach distracted her with pizza and Pac-Man and helped her find the life she has today.

“I wouldn’t change anything that happened to me,” she said. “It got pretty brutal at times, but it made me the person that I am. Every day, I wake up and feel that I am blessed. I could not be more blessed to be ale to do what I do. I love McKinney High School. I love these kids. Life could not be more perfect.”